Jorge Cantu

[Image Description]: Dr Cantu has brown hair and is wearing glasses. He smiles warmly at a student question at the Student Research Symposium at Northeastern Illinois University.

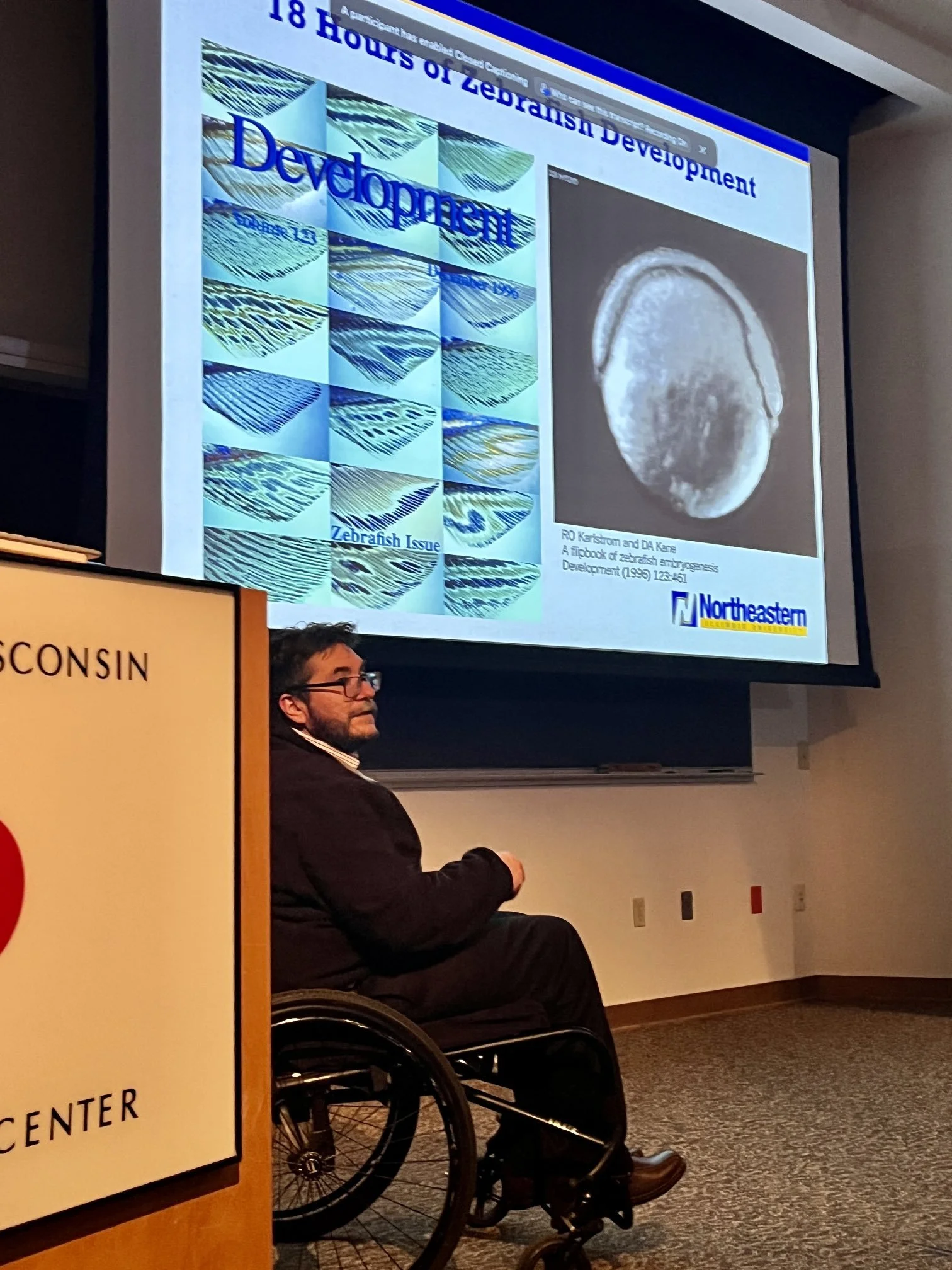

[Image description]: Professor Cantu wears a suit and is sitting in a wheelchair, delivering a presentation with slides on zebrafish development during a presentation of University of Wisconsin - Madison.

[Image Description]: Dr Cantu is wearing a sweater over a button down shirt and glasses. He smiles in a professional, black and white headshot for the Northeastern Illinois University website

A biology professor, neuroscientist, and zebrafish whisperer studying how the spinal cord is built.

What brought you to the STEM field?

I got into an accident when I was 17 years old. Throughout high school, my plan really wasn't to go to college. I had gone to vocational training to learn how to paint cars, so I was going to be an auto-collision repair technician. And then I was out one Sunday with a couple of buddies and I fell wrong in a dirt bike accident. I was out in the middle of the field thinking like a mechanic:, ‘I can't feel my legs, but all they have to do is get me to a doctor, and they can go in and they can fix it’. A doctor is kind of like a people mechanic.

And then, next thing you know, I'm in a hospital. I remember getting to the surgeon, and getting to the neurologist and saying to them ‘All right, doctor, you can fix this’. And they said ‘we haven't figured this one out yet’. That was the exact phrasing. We haven't figured this one out yet. I was stunned. How can you not fix this? This doesn't make any sense to me.

A lot of things happened after that, but slowly and surely I started to realize that I wanted to know more about the human body. That carried me through to go to college, to start taking biology classes, to start to understand the body. Nobody in my family had done anything like this before or gone into research. I thought, ‘well, I'm smart. I'm going to go to medical school, and maybe I'll be able to figure out how to become one of these human mechanics and fix people right’.

But for all the questions that I was asking, I kept hitting this wall. This isn't stuff we know yet. And that got me on a path to go into a PhD program, to want to learn more about science and try to figure out some of these things we don't know. And that's when I started digging into understanding the mechanisms involved in axon guidance, neuron specification, differentiation, that sort of thing. And that's also when I was introduced to the zebrafish as a developmental model. And ever since then I've been a developmental neurobiologist studying how the spinal cord is built.

Tell us about your STEM? What do you do, what do you love about it?

What excites me the most about science is that sense of wonder, or that phenomenon, or that thing, that unexpected thing, that you see every once in a while.

I'm at a teaching heavy, primarily undergraduate institution. My lab is very much a teaching lab. I see my role as training scientists, training undergrads to become scientists. My PhD advisor and lifelong mentor, he says he always saw me as a teacher. After I decided I wanted to go into teaching, he said “When you first joined the lab, you said that you wanted to repair spinal cords and traumatic brain injuries. What better way than to build an army of researchers to study the problem?”

In the beginning, what motivated me was my own injury and looking for a cure. This is the sort of thing that really drives you to do something. But with the impact I feel that I've had on my students’ lives, and my colleagues and my friends and my family, and everything else - there's so much more than just trying to find the cure to something. It's important work, I love it…but I think repairing people is better. Helping people learn to respect each other. To make better spaces for people, and make space for yourself. Those things I feel are what's going to lead to a happy life.

I'm also one of the active members of a foundation here in my local school district (that I actually went to as a kid). We do summer STEAM camps, we have an explorers program, things to get kids involved in STEM. We have an increasing number of Hispanic students in the district also, and English as a second language students, and my efforts there are to try to increase representation.

My interest in making disability more visible didn't come until later. When you become a faculty member (especially if you're a faculty member from a minority group), you're invited out to speak at places because of that status. Afterwards you get to meet with students, and what I found the hardest was when I met with PhD and graduate students and I spoke to them about the things that they were going through. How could nothing have changed? It's been 15 years since I was the graduate student, and you're still dealing with the exact same stuff that I was dealing with. It was on the plane ride home from one of these visits that I thought, you know, my man, somebody's got to do something about this! And then as I'm thinking about it, I'm like, well, no, I think I should be doing something about this.

What accommodations allow you to thrive? What tips, tricks, or hacks work for you?

I've had students in my lab who have had different disabilities, which has made it easier for me to advocate for myself to get more accessible equipment in my lab, because I had students who needed them as well. There's something strange about being the person who needs the accommodations, as opposed to advocating for somebody else who needs accommodations. It's much easier for me to advocate for somebody else than it is to advocate for myself. And this is something that I'm trying to overcome.

I had a student who uses a wheelchair, and I remember him when he came to my lab for the first time, and he said, “I want to work here because I can reach all the microscopes, and I see you doing it, and I never saw myself in the lab until I saw you doing this stuff”.

The thing that changed my life that every lab should be required to have is the oculars that move. I don't know why every microscope isn't armed with this, being able to take the occulars and bring them down, it's life changing. And it's different from a video screen - that's not the same as seeing it with your eyes.

All of my benches are at my height, so I can just roll under them, and I also have cabinets where I can grab a handle and pull, and then the shelving comes down. There's certainly some things that, for storage, have to be up high, but I have a golden retriever reacher that can reach stuff on top. And every semester I have to get at least one tall student. But that's for everybody, whether you're in a wheelchair or not, I highly recommend that every lab gets at least one tall student.

I’ve also never had a problem asking my lab mates for help. That’s just part of the business of being in a lab together. You could ask even if you weren't in a wheelchair. You could ask your lab, mate, hey? Can you reach that for me? It never bothered anybody in my lab.=

What do you want people to know about being disabled in STEM?

There was some time where I didn’t want anybody to see me like this, in a wheelchair. And then later, I wanted people to look beyond my chair, look at the person. And now it's part of me, it's not something I can separate from. There are certainly things that I haven't been able to do because of my injury, and because of being in a wheelchair. But there are also places that I've gone, and things that I've done, and people that I've met and thoughts that I've had that I would have never had otherwise. I've now been in the wheelchair for longer than when I was not in the wheelchair, and I can't imagine a life without it.

Students see that I'm a person who uses a wheelchair, and then reveal things about their own disabilities. All these things that they deal with on a daily basis you never even think about when you're trying to teach them about mitochondria. These students need advocates as well, and without having to reveal themselves unless they're comfortable doing it. Some people are very open, but some people are not ready to tell you. And they shouldn't have to. We need a way where they don't have to feel like it's strange that they have to present that they require accommodation.

What advice would you give to someone with a disability looking to enter the STEM world?

You can do it. There's some of us out there that have done it. There's more of us out there that have done it than you think. We're just so spread out. More likely than not, if you are a person with a disability, there might be other people who have a similar disability. And there are some things that probably work for everybody: ramps, elevators, things that are good to have. But there's going to be some stuff that is unique to your disability and finding out how to advocate for yourself and specify the accommodations that you need is gonna help you out in the long run.

I wish that the world wasn’t going to push back as hard as they do, but the reality of the situation is that there is going to be pushback. and it's kind of our responsibility to push forward.

And hopefully, when we get to that position where we are the person that is making those accommodations, then we can be better. There's also a lot of allies out there.There’s people that are pushing back, but there's more people that will help you.