Dr. Laura Otter

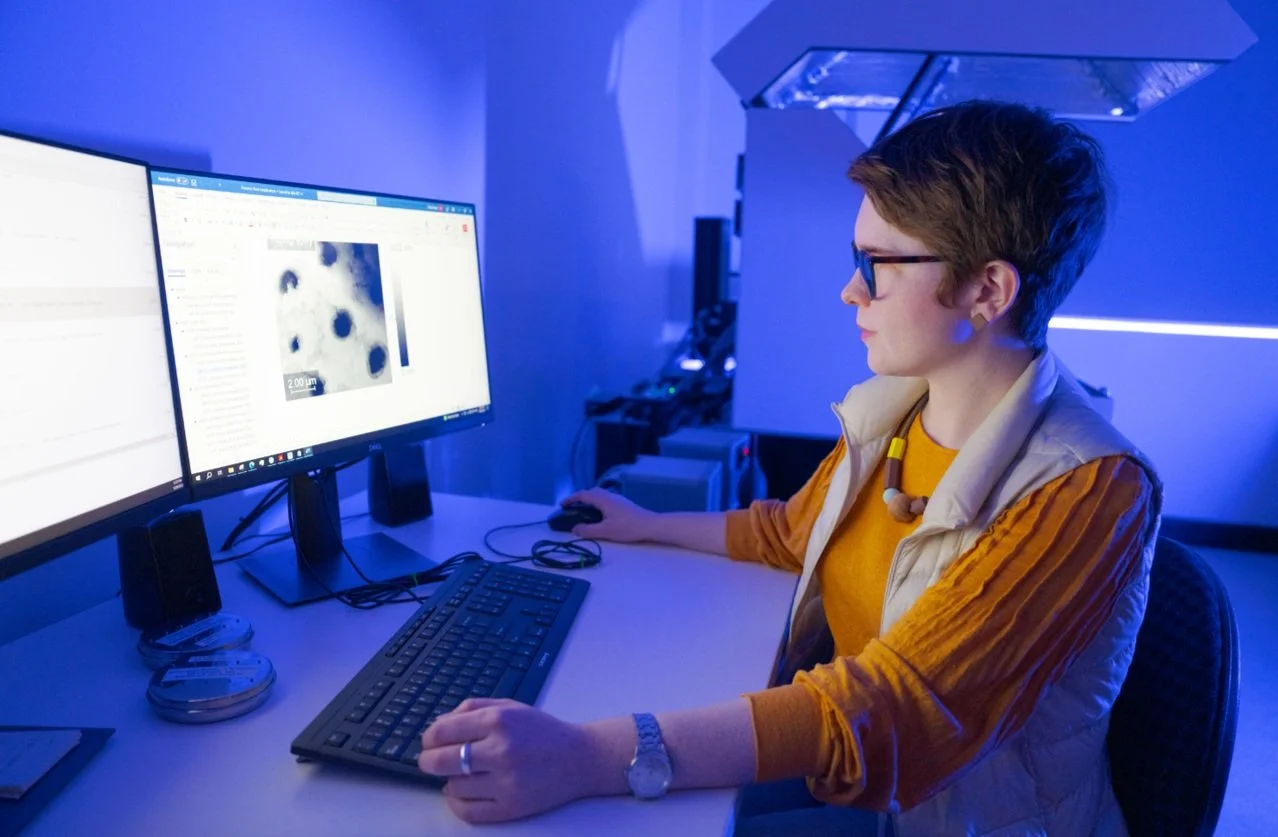

[Image Description]: Dr. Laura Otter works at a computer, examining a magnified microscope image of biomineralization in a marine shell. Dr. Otter is a woman with short brown hair, wearing glasses and a bright yellow shirt with an accent necklace. Photo: Nic Vevers/ANU

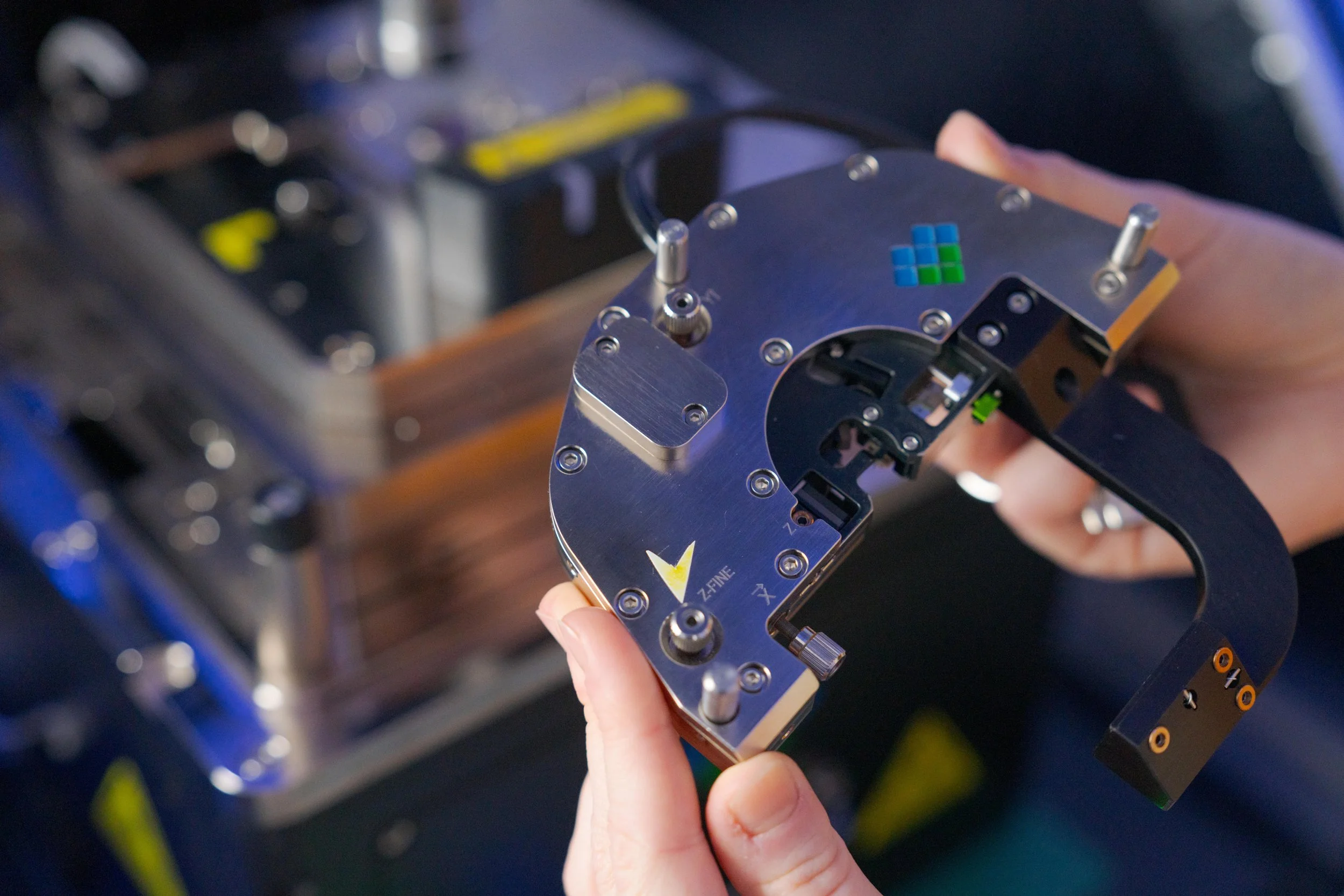

[Image Description]: Dr. Otter hold a critical piece of a microscope with neon visual markers on it in bright blue and green colours. The background is a blurred piece of equipment from the Photo-induced Force Microscopy lab. Photo: Nic Vevers/ANU

[Image Description]: Dr. Otter studies a piece of a marine shell while standing in the Photo-induced Force Microscopy lab, with a large metallic piece of equipment behind her. Photo: Nic Vevers/ANU

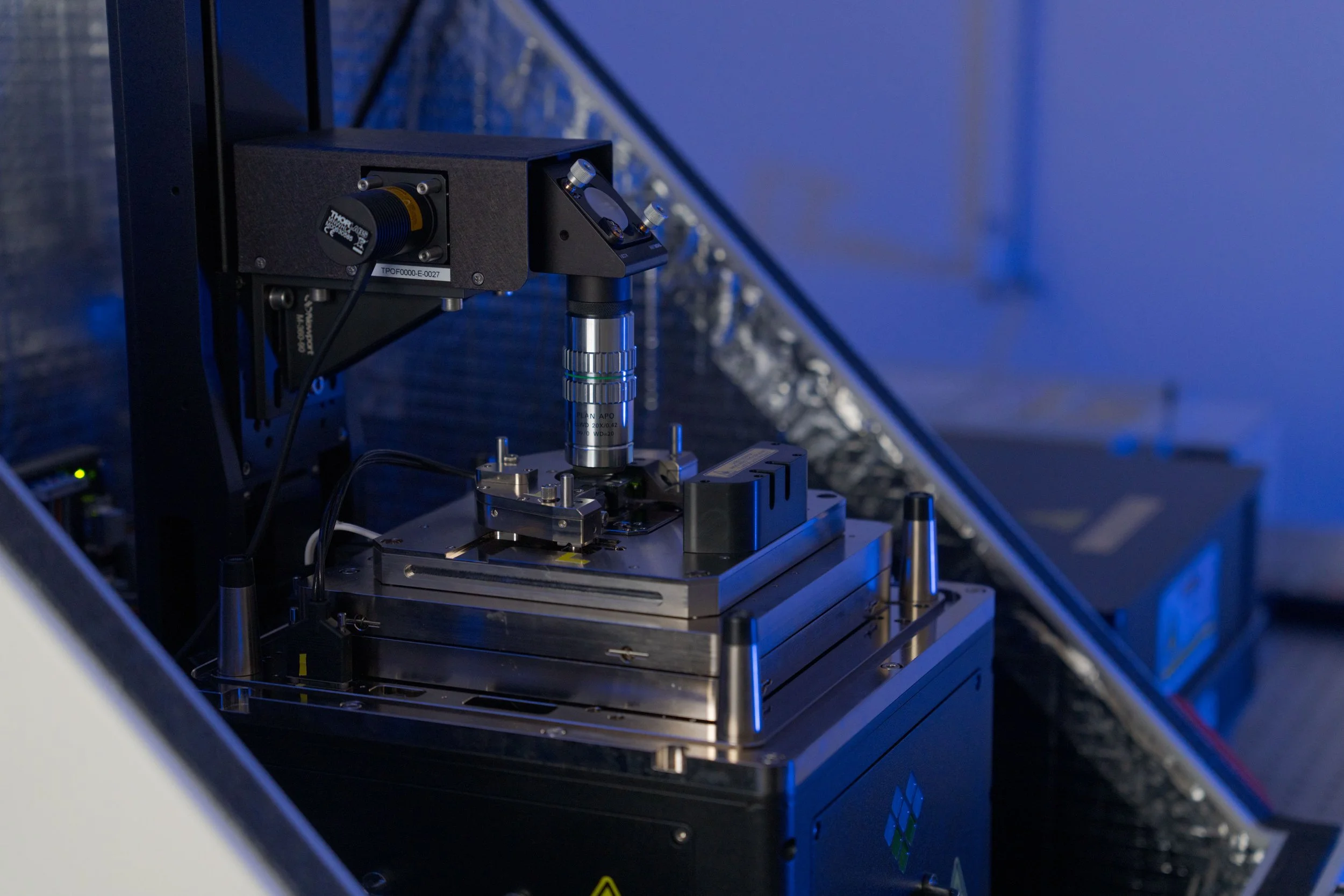

[Image Description]: A large microscope in the Photo-induced Force Microscopy lab is marked with small, neon visual markers to support accessible interaction with the equipment. Photo: Nic Vevers/ANU

[Image Description]: A close-up of Dr. Otter’s hand precisely positions a part of a large microscope. Photo: Nic Vevers/ANU

Meet Dr. Laura Otter (she/her), a legally blind biogeochemist studying calcification processes in marine environments.

Tell us about your work and research in STEM:

I am a postdoctoral researcher at the Australian National University’s Research School of Earth Sciences in Canberra, Australia. My research is interdisciplinary. By training, I’m a geologist and geochemist. Geochemists can look at all kinds of things, like volcanoes and rock compositions deep beneath our feet. In my case, I look at something different: I look at the little “critters” in our oceans that grow calcified shells, and how these shells grow across all kinds of different scales (macroscopic to atomic and everything in between!)

I try to figure out how those biomineralization processes work that lead up to the incorporation of trace elements and isotopes into the shells. We can also use this information to reconstruct past climate conditions if we look at the fossilized versions of these organisms. I mostly work on bivalves, including mussels and clams, as well as corals, and fish ear bones; these are all mineralised structures that record environmental conditions as they grow.

I use all kinds of different instruments to obtain this information. It's pretty interdisciplinary, in that I sometimes grow living organisms in aquaculture, exposing them to specific temperatures or trace element contents to grow very specific compositions of their shells that can serve as calibration material for samples collected in the wild.

As a geologist, caring for living organisms is quite unique and something I really enjoy. I also collaborate with colleagues from various disciplines including biologists, engineers, physicists, and material scientists. It's exciting to have a diverse team, each with their own disciplinary language, working together effectively.

Many marine species aren't accustomed to the extended heat waves of today's changing climate. One of our aquaculture experiments involves growing shells at high seawater temperatures. While mortality rates are high, we're studying shell growth before death and comparing it to survivors and control groups in cooler water.

Weather changes leave traces in shells. By examining the geological past, we can see how animals adapted to past climate changes, though not as rapidly as today. This helps us understand current species' potential adaptation and inform future predictions.

I was a nerdy kid, fascinated by the limestone tiles in our house, which contained fossils from a nearby outcrop in Germany. The little structures—leaves, spiral shells—gave me a glimpse into past environments. Imagining how these animals lived millions of years ago was mind-blowing. I became captivated by the concept of deep time and how life and the planet have changed over time. I thought I’d end up being a paleontologist studying fossil shells, but I’ve ended up looking at the modern equivalents instead, trying to understand how these animals grow their shells today, and how this applies to the ones that lived in the past.

What allows you to thrive in STEM?

I have a visual disability and am classified legally blind. That's also already a concept that's difficult to wrap one’s head around. It's really important to me to say that blindness is a spectrum. I have quite normal, central vision in one eye, but not in the other one. That imbalance gives me issues with depth perception. I don't see in our traditional sense of 3 dimensions. I have to work 3 dimensionality out by touching things for example and building that concept through muscle memory instead of just by relying on my vision.

On the other hand, I don't have peripheral vision. That makes seeing in low light conditions really challenging, because that's really the area in the eye that helps with night vision. In low light environments, people without this kind of visual disability will at some point stop seeing colours but are still able to make out the contours of things. For me however, it's either colorful or all black without that in-between. That makes navigating the physical environment more difficult for example when the sun goes down or lighting conditions are low. I sometimes use a mobility cane where I have the opportunity to feel the ground, which can really help identify stairs and curbs when I’m not familiar with the terrain.

It can also be really overwhelming when I’m on a busy street and everyone is rushing by - I hear people rushing by, but don’t see all of them, making it challenging to plan my route through the crowd safely and effectively. In those instances, I use what’s called an ID cane. It’s a lighter version of the heavy-duty cane that I mentioned before and doesn’t touch the ground. Instead, I will hold it in front of me so that other people can identify me as vision-impaired and will give me a bigger “bubble” of space when they pass by. So, unlike the heavy-duty cane, this type of mobility aid is really more about managing other people than managing my own path.

Otherwise when it comes to computer work and lab work in my academic life (two very visual tasks), it’s sometimes difficult to optimize those for my use when they’re in use by other people. On my own office computer, I’ve had a lot of help from an occupational therapist from Vision Australia, who has set me up with specialized computer programs that allow me to zoom into things on the screen a lot more, or read things out loud to me when I click on them. I can dictate emails or texts, and I can alter contrast when my eyes become fatigued.

Workplace adjustments have also been applied in our Photo-induced Force Microscopy lab with the help of the occupational therapist, who placed neon visual markers on critical parts of the instruments. This is especially helpful because many components are made of steel and other shiny metal alloys, and their reflections can blur the lines between parts. The markers help me efficiently locate and connect parts for example by aligning the markers on both pieces, which has been a game-changer.

I’ve been very much supported by my School director, who happens to also be my immediate supervisor, my School manager, when I wasn’t able to access fundings on college level as I am not an Australian citizen. It’s really important to find the circle of people who will be willing and in a position to support you and work together to reduce these kinds of barriers.

Learning to overcome my own discomfort in speaking up about my need for adjustments has been a bit of a journey and didn’t come easily to me as I am very keen to be independent. In the past, I could spend an hour trying to get one specific image on a microscope without knowing that someone else could have gotten it in a few minutes. I understand that comparisons can be tricky, but to me it’s been helpful to sometimes step back and observe how other people perform with the same equipment just to get a feel of how efficient they are. So, if I realize that I am working significantly slower, I will start thinking about alternative approaches or potential adjustments.

Something that’s been really encouraging is that my whole environment has always been very supportive and has helped me in many ways if I’m able to articulate my needs and ideas for improvements. That’s, of course, a privilege and might be different in other places, but my feeling is that people actually always want to help but just don’t know how. If you can make it easier for them to understand how they may help you or give them some suggestions and ideas, they’re usually very open in my experience.

I also faced challenges with fume hoods being too shiny and white, making it difficult to work with transparent liquids and glassware due to glare and depth perception issues. My school's mechanical workshop designed and produced vial holders in darker, opaque colors. This solution not only improved visibility but also prevented accidental spills due to their wide base. It's been a lesson in finding alternative, safer approaches, with the support from helpful colleagues.

Are there any accommodations or supports you wish existed or were available to you?

If you'd asked me a few years ago, I would have said some kind of computer program for optical microscopes that offers automated focussing as a way to make better and sharper images more efficiently. However, today, this has become a reality with a new instrument in our lab that can automatically focus and produce super sharp optical images even for larger image mosaics, and it does this fabulously! Now I can just trust in the process. I think I’m probably a lot more picky about my microscope images than most people without a visual disability, so I ‘m very keen about taking sharp images unassisted. I don’t have to ask people to help me determine whether something is in focus anymore on this microscope, which is really exciting! The software feature I am referring to is called ViewsharpTM and is part of the Horiba LabSpec software package on the new Horiba Soleil Raman Microscope. It's a very clever feature that finds the sharp contours very effectively. This is a really nice feature and I’d love to see more microscope manufacturers develop similar assistive features that help with finding focal planes independently.

Is there anything you wish you had known sooner when it comes to navigating the field with a disability?

Living in Australia has helped me explore this part of myself. Working with orientation and mobility specialists and therapists has enabled me to learn how to communicate my needs as a person with low vision more effectively and without oversharing. However, I wish I had learned these things sooner.

In the past, I didn't understand my vision was different and blamed myself for being clumsy, lazy, and slow and didn’t know there was a logical explanation for this. This hurt my self-worth at times. I wish I'd realized that there’s an actual physiological reason for these things earlier and that there are tools and strategies that really help a lot. Later, I learned that my vision is a spectrum that varies with lighting and how I feel.

I might have figured things out sooner if I had met others in similar circumstances. I hope people with disabilities will become more connected and visible, making it easier for those who are new to this to find peer support and navigate resources. Connecting with others who have had similar experiences can reduce feelings of isolation and provide valuable support, much like allyship.